Fiji Project, Suva, Fiji, February 3-13, 2015

Summertime in Fiji can be quite exciting. Steamy days and balmy nights aid the inclement weather over the island of Viti Levu. Like the electrifying storms, Island Culture Archival Support’s (ICAS) projects over the ten days throughout the city of Suva proved to be intriguing, fascinating, and a bit unpredictable at times. There were three institutions that accepted ICAS’ help: The Multimedia Archives at the Center for Flexible Learning on the tropical campus of the University of South Pacific (USP), the National Archives of Fiji, and the Oceania Marist Province Archives. Needless to say, every day was extremely busy with much movement during the day, as I had to leave one site for another. Fortunately, Suva is a city that can be easy to navigate. But, perhaps, more than anything else, the success of the projects depended on the considerate good nature and flexibility of our Fijian clients.

Multimedia Unit at the Center of Flexible Learning Archives USP:

One of the core missions of Center for Flexible Learning Multimedia Unit at the University of South Pacific (USP) is to provide support services in the creative production of quality and innovative educational media technologies. The unit offers a range of services including graphic design, web design, digital photography and sound recording. Thus, their archives consist of primarily audio-visual material such as reel-to-reels, videocassettes, audiocassettes, and photographs. Although a digitization plan with metadata standards has been in motion for some time now, the photograph collection of negatives, prints, and slides were badly in need of organizing and preserving. Our project goal, therefore, was to take physical control of the photograph collection and preserve the records. In time this will ultimately help staff gain intellectual control of the collection, especially as they grow deeper within their own digitization projects.

Working with staff members, Sereima Raimau and Bulou Guvati, we started with the black and white and colored prints. Although the photographs were in no original order, they were clumped together by subject in separate envelopes. The collection consisted of mostly events that took place at USP, or around Fiji. The dates ranged from the university’s beginning in 1968 to present day.

The first step in the process was to appraise the photo prints. We discarded duplicates and photos that were too damaged to be digitized. Naturally, this cut down on the number of photographs that we had to process. We were also given a set of priorities from Javed Yusuf, Manager of the Multimedia Team, of events that we had to keep. These included, USP’s Learning and Teaching Events, USP Research, USP’s Events (Graduation, Open Day, Pacific Week, and Anniversary Celebration), USP Field Trips, the Suva Community, and photographs of the Vice Chancellor’s Party. After we had appraised the photographs, we then gave each photograph a reference number that will be used later during digitization. During the next step we preserved them in acid-free enclosures. We placed up to five photographs in each enclosure believing that the archives’ environment was adequate enough to allow them to not stick together within the enclosure. Plus, it saved on the number of these hard-to-get enclosures. However, before the photos went into the enclosures, we wrote minimal information that helped identify the photo on the enclosure such as a title, date, and the photo’s reference number. This basic metadata will help later when placing the photos in a database as they become digitized. Our final step was to place the enclosures within acid-free boxes in order of their reference number.

Once we got a handle of the photograph prints, we looked at how we can process the negatives. We were hoping that we could follow the same guidelines as we had for the prints. Unfortunately, the processing of the negatives proved to be a bit more challenging than expected. The reason for this was that we found a lot more negatives than we originally thought were in the archives, and I did not have the right amount of supplies to properly preserve them. Most of the negatives are currently sitting in old plastic sheets and filed in three-ring binders. For now, it may be necessary to simply preserve the binders. However, the plastic sheets will definitely need to be replaced as soon as possible, as we noticed that the negatives are sticking to the sheets. Also, we suspected that many of these negatives would not be used in any future digitization projects, as they do not meet the criteria that was given to us. Many of these sheets did not have any identifying information. Thus, an extra step would be needed to examine the negatives before any appraising could be done. We concluded that processing the negative collection would require extra steps, more archival supplies, staff time, and, perhaps, volunteer help to process these binders of negatives. Therefore, we decided to postpone this part of the project until a later date.

We approached processing the slides in the same way as we did with the photographs. These were much more manageable than the negatives. However, since many of the slides did not have any identifying information, we did have to add an extra step in the appraising stage to view what they were. After we determined if the slide photo fell under our criteria list, we either processed or discarded it. Archival holders and boxes were used to organize and preserve the slides.

All in all, taking physical control of the photographs collection was significant for a couple of reasons. Perhaps, the most important reason was that it allowed the staff to learn what they have. Often, they will receive a request to digitize a particular photo and will, thus, have to spend a lot of time looking for it. Now, they know exactly where the photo is, and can retrieve it within a very short amount of time. During the two weeks we had processed over 1800 photographs. There remain a couple of cabinet drawers of photographs that are sitting in files. These still need to be processed. Another reason why this project was needed was that it trained the staff on how to handle and process photographs. Indeed, this knowledge will help to not only appraise, organize, process and preserve the remaining photograph collection, but it will also give them the proficiency and confidence to do the same for any new collections that may be donated to the multimedia unit in the near and distant future.

Salvaging Water-logged Material

The project at the National Archives of Fiji (NAF) was a bit different than the one that took place at USP Multimedia Archives. This archives was established in 1954 as the Central Archives of Fiji and the Western Pacific High Commission, and the name of the department was changed to the National Archives of Fiji after Fiji attained its independence in 1970. Its vision is to build Fijians through authentic and accessible archival records. The archives is home to the Sir Alport Barker Memorial Library that has a rich monograph collection on Oceania and Fiji. It also has a collection of rare books including John Hunt’s Fijian translation of the Bible printed in 1847. NAF has a staff of about twenty-five talented people and is considered, perhaps, one of the most progressive archives throughout the Pacific Islands. In fact, they have recently hired a group of individuals to manage their growing digitization needs of their collections. Also, they are one of the few archives that has a conservation unit that is graciously used as a training attachment for staff of smaller archives in the region.

On the second week of being in Suva, I spent the mornings at USP, and then made my way to the NAF in the afternoons to provide workshops for appropriate staff members. The first workshop was “Salvaging Water-logged Material.” This was a hands-on, open discussion event that taught participants how to recover archival materials after being soaked form a disaster. Flooding in the Pacific Islands region can come from many different sources such as cyclones, tsunamis, long term events like rising sea levels from global warming, ceiling leaks from heavy rains, and even a broken a pipe. It was important to talk about these kinds of flooding and to discuss disaster planning. Nevertheless, the workshop was intended to teach the last stage of a disaster plan and that is the recovery of materials.

I had brought in a couple of plastic bins and filled them with water. Then, I submerged archival materials such as books, (hardbound and softbound), photographs, documents, and maps. I refrained from using audio-visual material, as it would be too difficult to view or listen for any damage that the water may have caused. Plus, badly damaged AV material will most likely need to be sent to professional services. However, for future workshops I may add a few AV materials to see how the items and their cases hold up after being soaked with water. One note: all material used for this workshop were items that were withdrawn from a couple of different library or archives.

After the participants learned how to carefully extract each item from the bin, we then talked about the best way to recover each item. Since most of the archives in the Pacific Islands region do not freezers or funding to ship damaged items to freezers in another country, the best method for recovery was air-drying. The group agreed that air-drying would be excellent for drying small quantities of damp and partially wet material, as well as for drying wet materials in a major disaster especially if recovery services are unavailable. Additionally, we discussed air-drying a little more in detail such as: how it can take lots of space and people, the use of fans, and tricks to save space. We even talked about the importance of setting priorities to collections.

All in all, the workshop went very well. It was a bit unusual in the sense that participants got to get their hands wet. But, they really enjoyed it. The relaxed, thought-provoking atmosphere only aided to learning experience. I believe it was vital for them to get a chance to feel wet material and how the items respond to air-drying. Archival materials can become even more fragile after being wet or partially wet, and the skills that were learned during the workshop will serve them well in the event of a disaster. These new skills, hopefully, the participants will never have to use. But, you just never know. Finally, after we had emptied the material from the bins and went through the recovery methods, we let the items sit over night to dry. The next day we were delighted to see that all the material, with the exception of a couple of paperback books, bounced back to how they were before being wet. We concluded the workshop discussing better ways to recover the paperback books.

Preserving Photographs

The next day I gave a Powerpoint presentation titled, Preserving and Digitizing Photograph Collections. This is a presentation that I have given before at other organizations, and the NAF thought it would be appropriate for them this time around while I was there. Working with photograph collections has always been a passion of mine, so I am always delighted when an organization wants me to present the presentation. Nevertheless, the journey of this discussion allowed the audience to, first, look at the informational value of photographs and the reasons behind selecting them for their collections. Then, we examined the causes of deterioration, followed by basic photographic preservation and recovery after a disaster. Finally, we looked at the benefits and issues that come with a digitization project.

The one concern about presenting this Powerpoint to the staff of NAF was that it would come across as too basic for such a progressive archives. However, in this situation my hope was to introduce ideas that, perhaps, was not thought of before. Indeed, this happened a couple of times with the NAF staff. The first idea that was a topic of debate was when we talked about photographs as information value and how careful thought was required about which subjects have priority within the context of their archives’ acquisition policy. This actually turned into a round table discussion where we examined some of the criteria that may meet NAF’s priority standards such as: age, identification, provenance, quality, quantity, subject and uniqueness.

The second popular topic was about photographic storage. As was mentioned during the presentation, there are many different types of storage enclosures designed to protect different photographic formats and sizes. These include folders, sleeves, and envelopes. The choice of enclosure depends not only on resources but also the frequency that the photos will be handled for viewing and their current fragility. Naturally, the main issue was to show how preventative preservation can extend the longevity of records even in the intense environment of the Pacific Islands. Nevertheless, I brought a few examples of archival storage to show the staff. They found these quite fascinating, as it is difficult to procure enclosures due to the lack of archival supply organizations in Fiji, as well as in the region in general.

Overall, the presentation went quite well. It gave the NAF staff ideas to think about, particularly, in regards to their future digitization projects. Also, the staff learned that the value of photographs may be related to aesthetics, the richness of visual information, or general human appeal. Because of this, photographic collections often warrant more processing labor than other materials.

Disaster Management Plan

On the afternoon of the third day I arrived at NAF and met with the appropriate staff members to assist them in the design and implementation of a disaster management plan. Today, everyone who works in a cultural heritage organization in the Pacific Islands knows how important it is to have a plan. They understand that they are situated in, perhaps, one of the most volatile part of the world, and can be affected by many kinds of natural disasters such as cyclones, earthquakes, tsunamis, and even volcanoes. Unfortunately, like many archival institutions in the Pacific Islands, having a disaster management plan is something that is set aside to do at a later date, but never really gets done. There could be a number of reasons for this. The lack of staff, resources, and staff time, as well as not having the right proficiency can hinder them to draft such a policy.

Since NAF has a fairly new archival building, and added staff who were recently hired, they felt that the time was right to take a more proactive role in the attempt to develop and implement a disaster management plan. NAF also contains a library. Thus, we made sure that the librarian would be present during the meeting. The group looked at certain topics that would be placed in a plan designed for the needs of their archives. These included: Evacuation Procedures, Risk Assessment, Responder Roles, Network Response, Collection Priorities, and Recovery Plans and Methods. Although the discussions on all these topics were important, we spent extra time talking about Network Response and Collection Priorities. When we talked about Network Response, we are noting any organizations (within the community, the country, and internationally) that can help improve emergency performance, enhance communication, and assist in response and recovery after a disaster has struck. This could be a very crucial in these isolated islands of the Pacific. At the end of the meeting, each attendee had new ideas to help construct a proper disaster management plan for the archives.Oceania Marist Province

During my spare time in Suva I met with Father Roger McCarrick who is the archivist for the Oceania Marist Province Archives. The Society of Mary (Marist) is a Roman Catholic religions institute founded by Jean Claude Colin in France in 1816. In 1836, Pope Gregory XVI approved them on the condition that it would take charge of the mission field of the South West Pacific. Marists in Oceania were mainly working in the following eight areas (Vicariates) of Oceania: Bougainville (PNG), Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Wallis and Futuna, Fiji, Tonga and Samoa. The Society of Mary’s mission is to live the Gospel in the spirit of Mary, and is committed to prayer and community life. The Marists first arrived in Fiji in 1844 on the island of Lau.

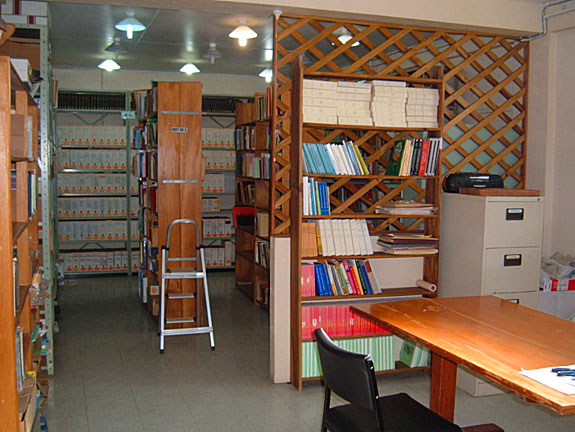

Although I did not have any specific project to do at the archives, I did spend time with Father Roger giving consultation on topics ranging from environmental conditions to database recommendations. Overall, the archives was well organized, and in good shape. The collection is comprised of two rooms that mainly contain correspondences, administrative documents, and photographs of the Marists in Fiji and throughout the Pacific Islands. The archives also poses as a small library, as, perhaps, forty to fifty percent of the collection are books that tell the story of the Marists and Catholics of Oceania and France.

At the time of my visit Father Roger was working on creating a database, especially for the books. Past volunteers have created box lists for the correspondence collection. Some of the records can certainly benefit with preservation work, and preventative preservation will definitely add to the record’s longevity. Nevertheless, a Website and digitization project of particular collections will indubitably enhance the archives’ profile. Additionally, these will encourage greater access to the collections. Moreover, the story of the Marists in Oceania can be told, and in turn, help reveal some of the history of Fiji, and the other Pacific Islands in which the Marists conduct their mission.